It’s still on my bucket list. Madrid’s Museo del Prado has a problem many galleries wish they had — overattendance. Last year the Prado broke records hosting 3.5 million visitors to the gallery. Of those visitors, almost two-thirds were “overseas visitors” — um, people like me. When I hear attendance caps, I do wonder how much harder it will be to get in?

Having established this new record for attendance, the Museum is now saying not a single person more. They have vowed to cap attendance, but haven’t yet said how. They also want to make the Prado more enticing to Spaniards.

The museum was originally founded in 1819, although it didn’t become nationalized and renamed the Prado until 1868. Like the Louvre, its collection is also capped by time period, finishing in the early 20th Century. Picasso’s Guernica (1937) was originally moved there after the dictator Franco died and Spain’s democracy restored, a stipulation of Picasso’s before the painting could return to Spain. In 1992, not fitting with the collection at The Prado, it was moved to the Museo Reina Sofia, also in Madrid. Instead you’ll find the best collection of Spanish art in the world, and surprisingly, the second greatest collection of Italian art after, well, Italy.

Wanting to go to the Prado goes back to my teens when my Grade 9 and 10 art teacher first did a class on Francisco Goya, who’s romantic works captured my imagination both in its subject matter and the way the paint was applied — later I was to learn how heavily influenced Goya was by Diego Velasquez. Some of his best-known paintings are at The Prado, including The Third of May 1808 (1814) which depicts a rigid French firing squad gunning down an irregular group of Spanish rebels from the Dos de Mayo Uprising in Madrid. The painting was commissioned by the Spanish government — apparently upon the suggestion of Goya himself — after the French had departed. Kenneth Clark described the painting as the first of the modern era: “the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, and intention.”

This week on the Artnet weekly podcast The Art Angle, Ben Davis, Kate Brown and Naomi Rea discuss the situation at the Prado, drawing the obvious parallels to the Louvre. I remember showing up at the Louvre in 2019 without a phone to find that entries were timed and that I had to purchase my tickets on-line and in advance. Being far from home, I managed to charm them to let me in anyway. That was the last time I travelled without a cell phone. Early in the day timed entries work, although in a museum as large as The Louvre, it catches up later in the day given those who arrive early don’t necessarily leave early.

Timed entry is a likely to be a solution to the overcrowding for the Prado, according to the discussion, but I wonder if will also mean higher charges from non-EU visitors, as has been done at the Louvre this year. Prices for overseas visitors to the Louvre increased by 45 per cent — to 32 euros (about $52 Canadian). Given the talk about all the overseas visitors, this would not surprise me.

Of more interest was the discussion around the housing of the star attractions. In Paris, the Louvre has created a dedicated room only for the Mona Lisa. When I visited, it was in a temporary location in a large room lined with other masterpieces that were difficult to look at given the large snaking line makings its way between the crowd control ropes. It effectively not only made the Mona Lisa difficult to view, but everything else in the room as well. The line also snaked up the stairwell, making the entire section of the Louvre difficult to get around. In the end, I found the line and the reaction of the tourists far more interesting than the painting itself (its small — 77 x 55 cm). By the time I got to the cattle pen closest to the Da Vinci, it was still a great distance away and most people just pulled out their cameras and took pictures as if they had never encountered a picture of the Giaconda before.

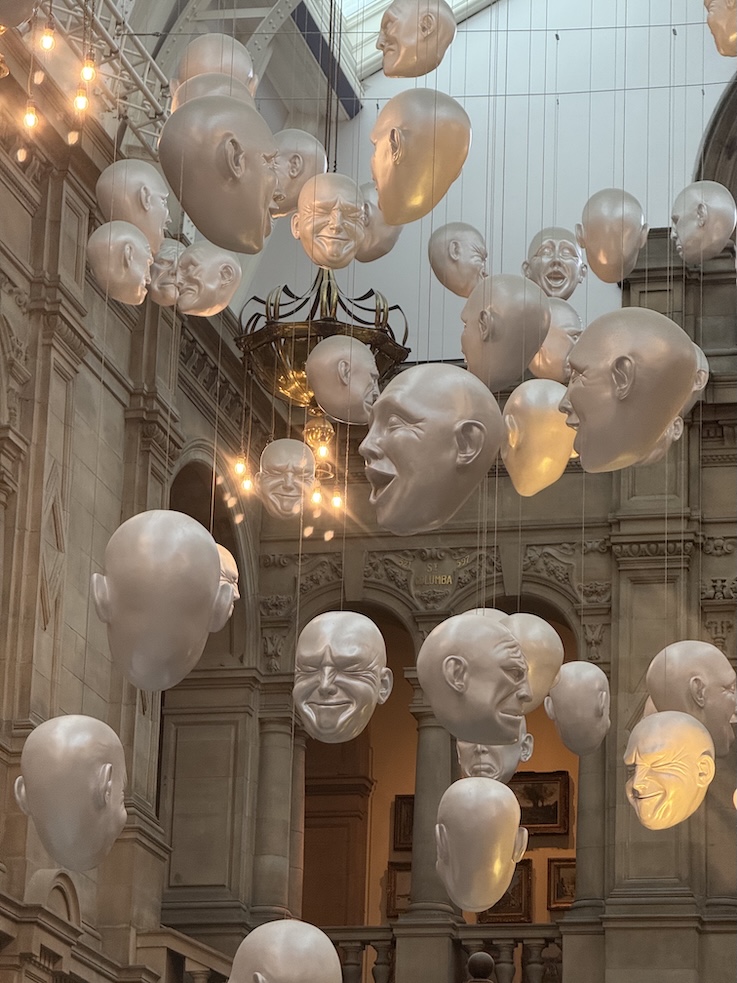

Many galleries have chosen to do this — this fall we saw Glasgow’s Kevlingrove hive off its star attraction — Dail’s 1951 painting of Christ of St. John of the Cross. The room was not that large and it had the feeling of entering a peep show, but it did allow us to view the rest of the collection without any problems.

Star attractions do tend to cluster people — a reality more noticeable at the Musee D’Orsay where some of the most beloved impressionist works were difficult to approach for the crowds in front of them. The Artnet discussion had suggested that some of these works might instead travel to the regional galleries in Spain. I can’t imagine art pilgrims making the trip to the Prado to find out their favorite piece is now in Seville. It also raises questions about the safety of the work itself given that kind of travel.

These museums also have to be aware of what the crowding means not only for visitor experience, but the risk to the artworks too. In recent years there have been a number of valuable museum pieces that have been damaged or destroyed by visitors. And let’s not forget when the staff walked out of the Louvre, one of their stated concerns was the difficulty of doing their job amid all the overcrowding.

One can’t help but think that such galleries are going to be increasingly challenged in the near future, as travellers choose the EU over the United States as their preferred destination. This after we just got over the post-COVID travel wave. Canadians may be among the first to say they won’t travel to a United States for obvious safety reasons, but they won’t be the last either.

—

Have been painting a lot in the studio this past week. Several pieces will likely reach conclusion soon. It was my intention to produce a number of affordable “smalls” (12″ x 12″) in anticipation of the Scugog Studio Tour May 2-3, but I am finding that the time required on them is not that different that a 16″ x 20″ painting. Watch for a future post on the dilemmas of size. Meanwhile, if you want to look at my stuff without all this palaver, click here.