When I entered Toronto’s Scarlett Heights Collegiate Institute in the early 1970s, I thought it was normal that a significant proportion of the school’s art program was in art history. I loved it, and the education I got in grades nine and ten set me up for my eventual enrolment at the University of Ottawa’s art school, then on to the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, where I received my BFA.

After my parents had moved from the West to the Eastern side of Toronto, I changed high schools, and to my disappointment found that classes were all about making art, not studying art. How can you make art without knowing about its history? That continued when we moved once more to Ottawa, where in Grade 13 there was no art history either.

It turned out my art teacher at SHCI was legendary for the art history classes he taught. He told us that his slide decks were frequently loaned out to other schools even though they belonged to him personally. He had travelled to many of the world’s great art museums to photograph the paintings and sculpture we studied in class. In the Louvre I had a particular moment, recognizing many of the paintings we painstakingly studied from Mr. Samatowka’s slides. There was one particular requirement in his art history classes — that we take home short art history essays he gave us and hand write them out. I don’t know if that was a way of burnishing them in our minds, or whether it was his way of making sure we read them? That was our home work. Other artists speak about Mr. Samatowka’s influence on their decision to enter art school and take this up as a profession. But as I learned, this level of attention to art history was an exception, not the rule. I lucked out, especially being a working-class kid who at that point in time had never set foot in an art gallery.

November 27th London’s Courtauld Institute of Art (affiliated with the University of London) announced it was establishing a foundation to raise 81 million pounds (about $150 million in Canadian dollars) for its 100th anniversary in 2032. A big part of that is about enhancing the physical site, but scholarships in art history were to be a big part of the plan given the perceived decline in art history studies . The original article noted that across the UK only 19 “state or non-fee paying schools” were now teaching art history to 16-18 year olds — all of them in England.

A day later the story was appended with a note to say that the number of student entering A-Levels in Art History was virtually the same between 2016 and 2025. There had been no decline in the interest in the topic, even if the outlets to study were diminishing for English teens.

In art historian Kate Bryan’s most recent book, How To Art, she speaks about growing up as a working class kid and not having exposure to art beyond what she could see in books. As she writes: “I just didn’t know anyone who talked about art, owned art, or visited museums. I wasn’t related to anyone who’d gone to university. I didn’t have much money for train fares, and I didn’t know that public museums in the UK are free.” She said that her art world experience prior to university was a single school trip to the Tate. She ended up becoming an art historian quite by chance, stumbling across the History of Art gazebo at an education fair at the University of Reading.

I felt much the same. My parents would have not even considered taking me as a kid to an art gallery. It’s not somewhere they would have gone by themselves either. Curiously, late in life, I took them to a folk-art gallery in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, of which my mother spoke way too loudly about the work on display, proclaiming even she could do better. I was shocked by the emotion, even if it was to trash everything she saw. In the end, she did go back home and started making her own wonky paintings. I have one on my wall in this room. That’s the power of art — even if you may not like what you are seeing on any given day. I think it unlocked something in her.

My Dad did show all of us how to draw, and there were these art books around the house that looked like something a grocery store would have issued. I have no idea where they came from. I was always encouraged to draw until I let him know that I wanted to go to art school. Suddenly the encouragement stopped. I couldn’t make a living from art, he told me over and over again. Going to art school was my big act of rebellion. My story is not that unusual among working class kids. And yes, in the end, I did make a living despite graduating with a BFA.

It amazes me how few parents actually do take their kids to public galleries. In the UK the public galleries are free to everyone. In Ontario, provincial residents under the age of 25 are admitted free to the AGO. If the parents want to skip the stiff $30 entry, the first Wednesday of the month is free for all visitors. You don’t have to be rich to look at art.

Does studying art history matter?

Well perhaps we can answer that question with another: does studying English matter?

I think the answer is of course — studying English not only sharpens our literacy skills, but helps us come to a more in-depth understanding of the world and ourselves. It rounds us out by getting into the heads of different writers and exposing us to alternate points of view. Life is not black and white. By becoming better readers we also become better writers. If you can’t express yourself, life can be full of frustration.

Is visual literacy important in the 21st century? Look around you. Do you understand the non-written cues in what you see every day? Are you missing the symbols? Do you get a feeling from looking at specific pieces of art that go beyond a simple narrative (eg — its a picture of a tree)? What does it mean to you?

I once took a workshop with musician and academic Tom Juravich, who suggested that if we want our audience to come to a deeper understanding of what we are saying, then the arts are a way to achieve that. How many of us have ever been moved by a song? A movie? A play? A novel?

How many people had their lives completely changed by walking through the doors of a gallery?

When I went to the University of Ottawa, the old National Gallery of Canada was just across the canal. Admission then was free, and I spent many hours there looking at art. It had a profound effect on me, including realizing that as an artist (or then as an art student) that I belonged within a continuum of art. Like all history, it brings a certain sense to the present.

Art history is not a frill. It’s not elitist, although it should be a clue that the elite see it as important for their own children to get a well-rounded education, including art history. It should be part of everyone’s education. We should all talk about it.

—

Its been a hectic few weeks — I should have a new painting up on this site by tomorrow. Meanwhile, if you want to look back on my output over the last year and a half, click here. And if you are anywhere near in the Eastern GTA, please visit the group show I’m in at the Station Gallery: Rare Form. It is open to the public now, although the official opening is December 17 from 7-9 pm. Hope to see you there!

Talk about timing — I had just finished posting this when I received a fundraising letter from the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa. In it, Alix Voz, the new director, writes: “At RMG we believe that art is not a luxury, it is a necessity… Art invites us to reflect, feel inspired, share stories and ideas, and discover new ways of seeing ourselves and one another.” Well said.

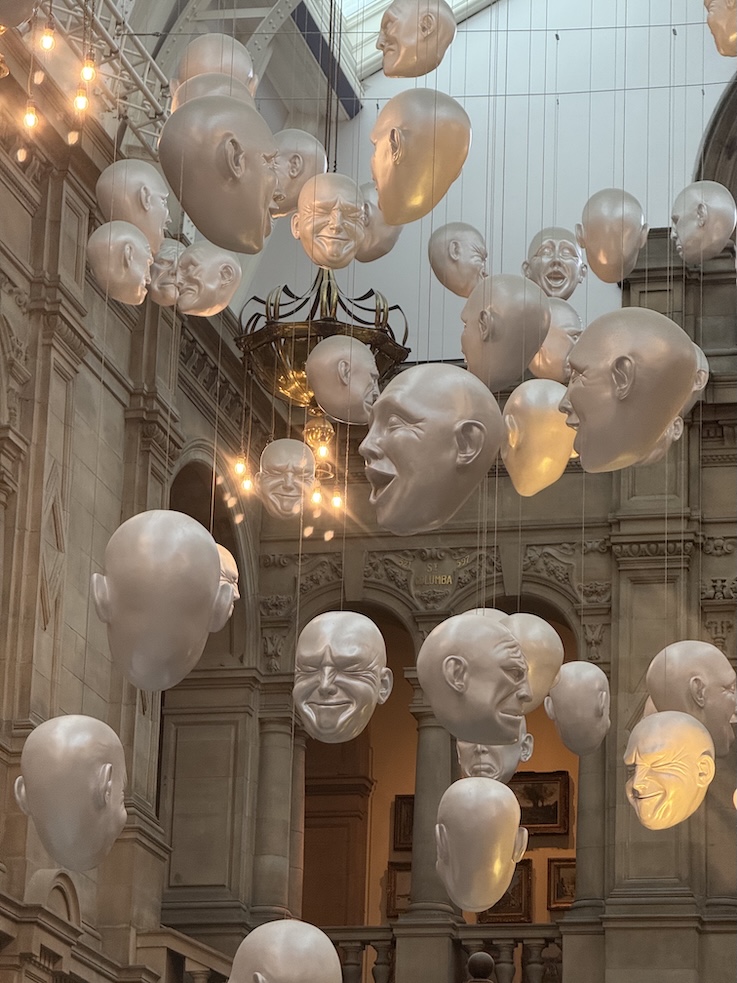

Image for today’s post: The Heads (2006) by Sophie Cave at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

Leave a comment