Imagine creating a piece of art that resulted from an interpretation of a coffee stain? The trick may be to use good quality coffee.

Last night I attended a meeting of the Oshawa Art Association in which artist and animator Lisa Whittick (click here) spoke about her methodology behind these coffee drawings? paintings?

At first I wondered if she had a caffeine issue to have so much coffee dripped on watercolour paper, but as she demonstrated, she actually takes a brush and smears the coffee on, including some splashes from a paint brush dipped in a cup of coffee. I hope she remembers to stop drinking from it at that point.

After the coffee splashes have been given an opportunity to dry — sometimes she splashes it more than once depending on the outcome — she looks for potential images in the splashes, much like one might interpret a rorchach test.

It did occur to me that given her coffee stains were not entirely accidental, that one could do this with just about any medium, including paint. But coffee is her medium of choice — Whittick explaining that she liked the colour.

After she works out her scheme, she downloads some drawing aids to help her visualize the picture. In this case, she had seen a porcupine and some zinnias as inspiration from the coffee splotches, and subsequently came to the presentation prepared with some computer print-outs of both.

From there she started working into the coffee stains with a black pen, varying the size of the nib depending on the need. That included, in some cases, simply drawing a line around some of the splash marks.

From there the process is back and forth, as she moves between a set of pens, some conte, and an acrylic wash. Worried that the conte would overpower the coffee stains, she applied it gently using a Q-Tip. After about a forty minute presentation, she had a finished drawing — well sort of. Like many artists that I have referenced in the past, deciding when it is done is always the biggest challenge, and Lisa would start to answer some questions, then realized she needed a bit more white paint, or some darkening with a thicker pen, or a little bit more of something else. We’ve all been there.

What’s interesting is that the process is a random way to start a piece, letting the coffee stains dictate what the subject matter is, although it is clear from looking at her work that there is a fantasy genre she largely likes to work within, so while it is random, clearly her own interests are not entirely lost. She explained at the start that it got over her fear of a blank page.

I asked if her if she ever placed a coffee cup on the page, to have the addition of coffee rings to work from. She was amused by the idea, but had never done it.

It reminded me of my art school days when I would drink so much coffee on my studio days that I was literally shaking towards the end of the afternoon, which in itself created a certain amount of dripping. The school custodians must have hated me.

Whittick does these drawings as a means of keeping her creativity alive and sees it as a means of relaxing after her much more demanding career in animation, where as she says, it is a team effort that precludes individual expression.

If you want to give it a try, Lisa is delivering a workshop on September 28. Click here for more details.

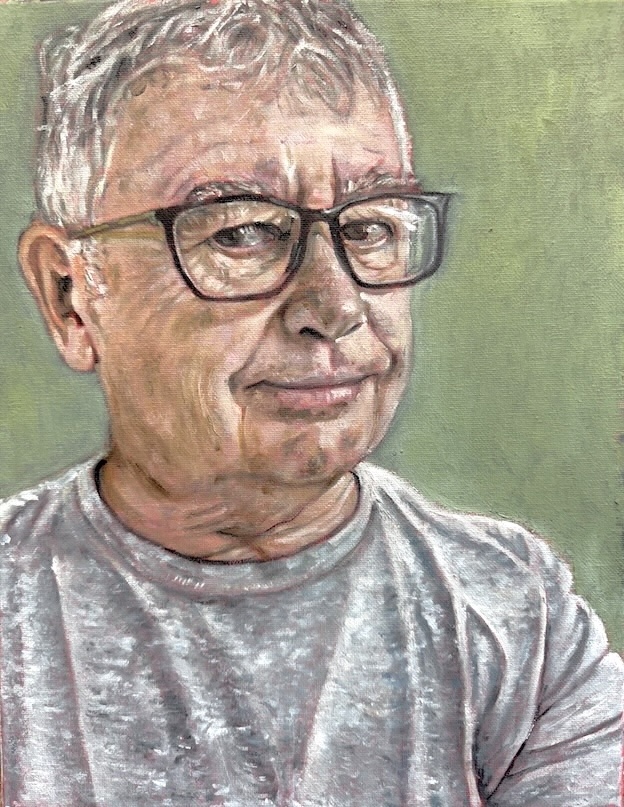

Happy accidents are not entirely new. One of best practitioners of happy accidents I have seen is Christian Hook, who won UK 2004 Portrait Artist of the Year title. The winner of that competiton won a commission to paint actor Alan Cumming for the National Portrait Gallery in Scotland.

Hook engages in a process that involves doing and undoing, creating what appears to be a straight-forward portrait or landscape, then messes it up and works from there, taking the random scratches or slashes as new information to work with. The end result leaves a piece that is figurative but also has abstract elements about it. It’s brilliant.

It’s a little different from Whittick is doing given the randomness can take place in the midst of the process, not just at the start.

In the documentary (on Amazon Prime) Hook engages Cumming in the process, including giving him the materials to make his own marks.

When we visited Edinburgh in 2022, the Portrait Gallery was a key destination for us to see the Cumming portrait. It is stunning to see in person. Photographs of it just don’t do it justice, but you can none-the-less get a peek at it on Alan Cumming’s website.

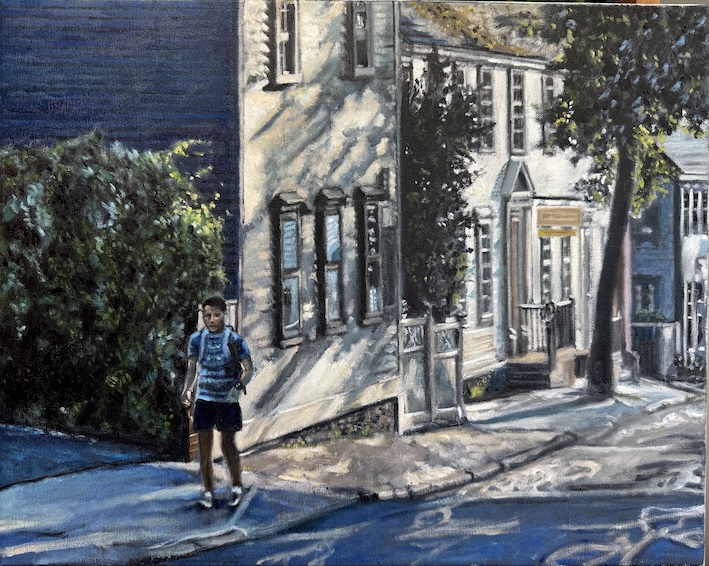

Today’s Artwork: I looked through my files to see if there was anything that I could describe as a happy accident. Have to say that happy accidents scare the heck out of me. I’m far too much of a control freak to randomly undo my work in progress and create something new from it. Instead I offer up something else that scared me too — one of the few pastels I have ever done, this one looking across Long Lake, a Provincial Park on the outskirts of Halifax. You can tell why I’m an oil painter from this. I did use the drawing as the basis for a painting later that year. I’ll show it on the next post so you can see the difference. Always a trick to may you come back again!

—

Don’t miss another post! Subscribe for free. Want to look at more of my stuff? Everything from late 2024 to the present is on my gallery, just click here. Meanwhile, consider joining your local art association. You’ll not only meet new like-minded creators, but get some good ideas too.